The world of European currencies

Economy 15 February 2016For a long time, European young travellers and commuters have been used to exchange money when travelling around the Union. For them, it would not be strange to own several different currencies in their wallets, but if you are an American and you decide to travel from Denmark to Slovak Republic in your Euro trip adventure, an unpredictable scenario might occur. If we exclude the possibility that you can be charged more than the official exchange rate(s), nothing else remains except to note that you will experience a dramatic different currency rates in different EU Member States.

Beyond the several seconds of currency exchange process, dozens of things have been initiated. And while you are making your first steps to the European soil, an average European citizen will advise you to exchange your dollars into Euros, with an indisputable argument that “it will work everywhere…okay, maybe not in Czech Republic”. When you exchange your money into Euros, you have entered into a new world of processes which cannot be observed so easily.

The European “currency system” (not officially established) consists of 28 different currencies within 50 states of the pan-European space, of which one of the most important is surely Euro.

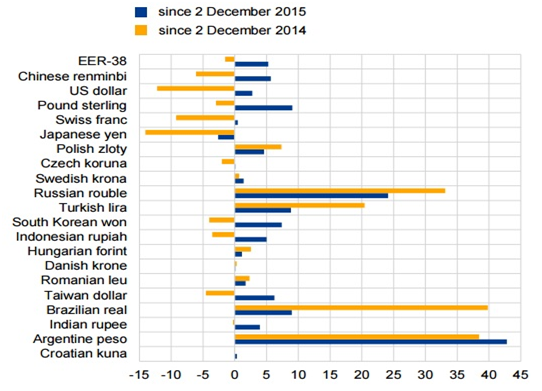

This chart below shows the differences in exchange rates for the Euro both in the national member states and other trading partners of the Union.

NOTE: EER-38 is the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro against the currencies of 38 of the euro area’s most important trading partners.

What it can be concluded from the chart, is that European currencies are more stable towards the Euro, than the all other non European currencies. The indicated period was set up for 2014 and 2015 fiscal years. Nonetheless, it still does not mean that European financial area is completely stable. On the contrary, European Central Bank has a very extensive approached methodology when analyzing the fiscal and monetary system(s) within the Continent. The introduction of the Euro has led to extensive discussion about its possible effect on inflation.

On the short term, there was a widespread impression in the population of the eurozone that the introduction of the Euro led to an increase in prices, but this impression was not confirmed by general indices of inflation and other studies. A study of this paradox found that this was due to an asymmetric effect of the introduction of the euro on prices: while it had no effect on most goods, it had an effect on cheap goods which have seen their price round up after the introduction of the euro. The study found that consumers based their beliefs on inflation of those cheap goods which are frequently purchased. It has also been suggested that the jump in small prices may be because prior to the introduction, retailers made fewer upward adjustments and waited for the introduction of the euro to do so. But a small inflation in such a long period of time (more than a decade) will not affect a wallet of an average young American in his Euro trip.

Besides his generous contributions to the exchange office owners (to earn more money on his transactions), the fact that he initiated currency exchange process means that European financial system indeed works in practice effectively, but what is being missed?

European Central Bank does not have any regulations or mechanisms through which it can control the exchanging processes within the Union. Nor the national banks are ready to limit the maximum (or minimum) exchange rates for the other national currencies in their own states.

So, it can possibly happen that in Hungary, a young American get almost 310 Hungarian Forints (HUF) for 1 euro, but if he suddenly needs forints while he is shopping in Nowy Swiat street (Poland) he will be given 270 Forints for 1 Euro. The fact that less than 20% of money can be given for the same transaction in the different member states, can make the most sober American to reach out for a famous Balkan`s drink – rakija. And while an American is visiting the region, he will definitely need one more shot of the drink, when he realizes that he will be even more charged on the transaction for Serbian Dinar (RSD) in Croatia, Bosnia or Montenegro, and vice versa. For instance, in Croatia, he will get 7.66 Croatian Kuna (HRK) for 1 Euro. But if he forgot to exchange all his Croatian money when arriving to Serbia, he can exchange them for Euros in Belgrade for clearly different exchange rate, and of course be given less money.

As he approaches to Bulgaria, he will experience a fatalist drama. He even will not be able to exchange his Croatian Kuna for Bulgarian Lev, due to the fact that Bulgarian exchange offices are not providing the exchange for Croatian currency, though both Croatia and Bulgaria are EU Member States!

None regulations have been even suggested or proposed to regulate this area of financial commerce. The one of four freedoms which is entitled to be the corner stone of the EU, free movement of services, guarantees that Europeans can do their businesses in different currencies in different member states. If not all 28 member states are full members of the Euro Zone area, it does not automatically mean that they can make the obstacles in currency systems. A new and innovative supranational legislative must be a major part of the solution and the issue highly ranked in the European economic and financial agenda.