Stressed bank for stressed people

Economy 17 November 2014On October 26, the ECB released the results of its “comprehensive assessment” on the European banking sector. It is composed of an Asset Quality Review and a Stress Test. The first, as the name suggests, estimates the quality of assets held by banks. The second one models the resilience of banks under adverse scenarios. 25 banks failed the exercise, 13 of which will have to raise additional capital, and EUR 136 billion of additional non-performing loans were uncovered by the ECB – bringing the total to a staggering EUR 879 billion.

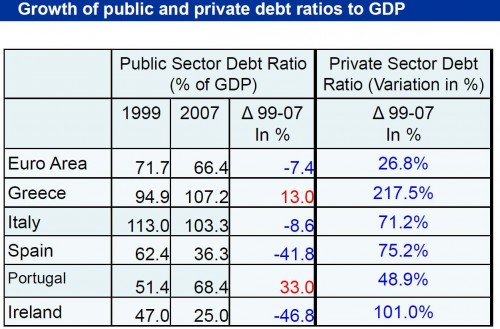

Why is this exercise important? It is important because the exponential growth of private debt in the period before 2008 is precisely what led to the crisis.

Such assessment, by monitoring the situation and imposing limits to banks, should prevent the replay of the past.

Note that the conditional is mandatory. True, after the crisis, measures have been taken to strengthen banks’ regulation such as the establishment of the Banking Union. Although, according to some, it will have little benefit because it fails to provide an adequate common resolution fund that would completely severe the link between banks (which operate across borders) and national government budgets (which, in case of failure, are called in to bail them out).

But the biggest problem rests elsewhere. For as tight as regulation can be, it cannot by itself ensure that assets’ value won’t crumble. It is perhaps worth recalling that the quality of a lender is strictly related to the quality of its borrowers.

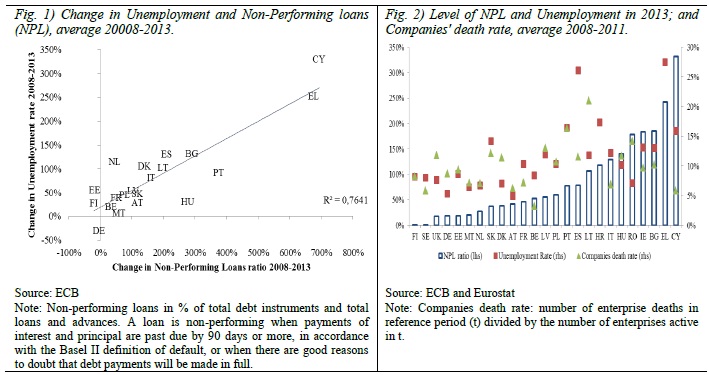

Not surprisingly (Fig. 1), those Member States where the unemployment rate has increased more dramatically are also those where the NPL (Non-Performing loans) ratio recorded the biggest jump. There is also a rather evident (though less significant) correlation between the level of NPLs and the average companies death rate (Fig. 2). In other words, Member States that suffered the most in terms of lost output and employment are those where the banking sector is under greater “stress”. When borrowers sink, lenders struggle to stay afloat.

In conclusion, the ECB is certainly doing a valuable job keeping banks in check. But policy makers should start asking themselves a classic chicken-and-egg question. What comes first, a stressed bank or a stressed economy? Depending on the answer, perhaps “bailing out” borrowers – by promoting employment for workers and growth for firms – may turn out to be a longer lasting solution, also for creditors.