Nord Stream Two. A twist in EU energy market?

Opinions 24 November 2015On the 4th of September, a crucial event for the economic and political future of the European Union took place.

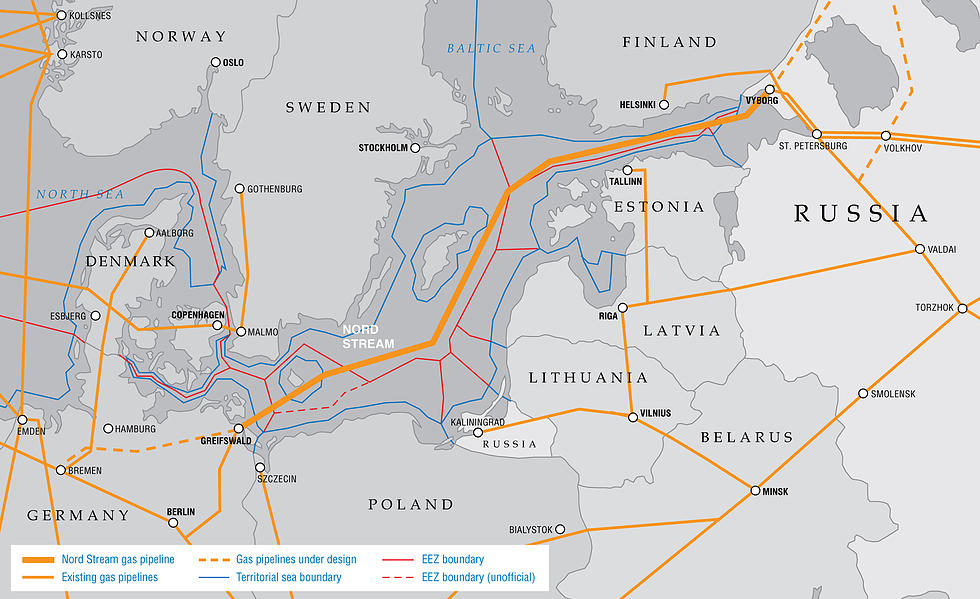

At the Economic Forum in Vladivostok, Gazprom, the Russian leader in the energetic industry, signed an agreement with Germany and some Western European companies, in order to reactivate the four-years old Nord Stream Two pipeline project. The new gas pipeline will be parallel to the already existing Nord Stream One, lying on the seabed of the Baltic Sea, and it is going to be the world’s biggest natural gas transportation project in terms of length and capacity.

The construction plan was initially announced in 2011/2012 through non-binding agreements of intent, but the European economic downturn and the Ukrainian crisis forced the parties to shelve the project. The agreement signed on September, however, is binding. The main goal of such a project is to bypass Ukraine’s gas transit system, its continuation through Slovakian and Czech corridors and potentially Poland’s too, basically connecting Moscow directly with the “Old” European Union.

This arrangement should be interpreted in the light of the recent developments in the EU-Russia relations after the Russian Federation’s involvement in the Ukraine conflict. From this perspective, Nord Stream Two represents a success for Russia, which accomplishes its strategic goal to maintain a sound economic relationship with Europe, despite its tumultuous relations with the Union and the sanctions regime applied after the Crimean invasion.

Furthermore, this project significantly strengthens Moscow’s bargaining power in its negotiations with Kiev, since it will allow Russia to consistently reduce the amount of gas transmitted through the Ukrainian pipelines (in view of a complete shutdown by 2020). Moreover, Russia hopes that this new cooperation between Gazprom and the principal European energy companies will increase its lobbying capabilities within the EU, giving Russia the chance of gaining important political advantages.

From the German point of view, Nord Stream Two represents a real evolution of the Berlin’s role in the European energy market. Germany is going to gain the status of “energy hub”, becoming the primary center for storage and distribution of Russian gas in the Western Europe. This could provide new opportunities to German energy companies such as E.ON and RWE, which are experiencing hard times in adapting to the rapid expansion of the renewables on the German energy market.

However, the deals signed by the European companies and Gazprom collide with the aims of the EU’s policy on energy supply. The European Union’s plan, over the last year, entails increasing diversification in gas supply, strengthening the economic cooperation with Ukraine and reducing dependence from Russian gas, as implied in the provisions of the European Commission’s strategic documents.

In this sense, the development of the Nord Stream Two agreement is emblematic of European companies’ skepticism on the EU policy and of their attempt to contribute to shape it. Furthermore, it shows the lack of common interests within the EU related to the gas cooperation with Russia.

The European Vice-President for the Energy Union, Maroš Šefčovič, raised a bunch of questions on the project: “Does Nord Stream correspond with the EU’s supply diversification strategy? What does it mean for Central and Eastern Europe? What conclusions should be drawn if this project aims to practically shut down Ukraine’s transit route? All projects of this magnitude would have to comply with EU legislation.”

Furthermore, the EU Energy Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete stated that, since Nord Stream Two does not comply with the EU supply diversification policy, it could not be considered a “priority”; thus he diplomatically asserted that the project will not receive any EU funding.

On the one hand, Eastern Europe has taken a position against the project, sharing the same doubts raised by the Commission. Countries like Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia and Czech Republic argue that such an agreement would threaten their own status as conveyance States. On the other hand, Western European countries and their principal firms support the agreement, contending that reactivating the gas cooperation of Russian would be necessary to meet future demand.

This divergence of opinions finds its origin in the fact that the two European “blocks” have developed significantly different political and economic relationships with Russia during the history. In my opinion, until the European natural gas market is fully integrated, the two parties will not be able to agree about the “right” amount of gas Russia should supply to the Continent.

In the meantime, it will be very complicated for the opponents of Nord Stream Two to block the pipeline realization, since Germany and Austria already support it and Gazprom just needs the construction permits from the Scandinavian countries, that promptly backed the realization of Nord Stream One in the past.

Jacopo Bacchiocchi

European Generation