In other news: China’s 28 trillion dollars small debt problem

Economy 13 July 2015With all the eyes set on the unfolding Greek drama, which we accounted for already in this newsletter, few people seem to have paid attention to spectacularly scary news coming from the Chinese financial markets.

The unbalanced Chinese economy

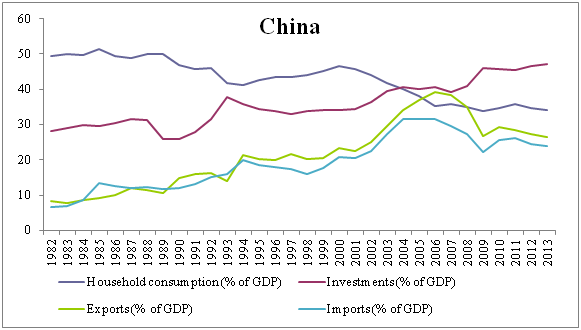

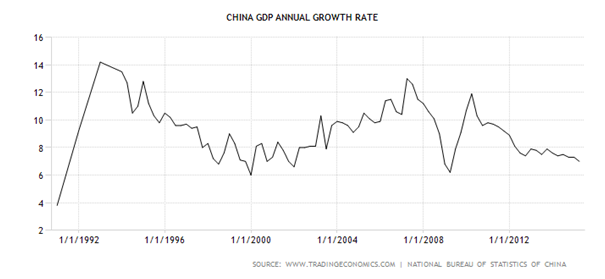

The Chinese economy is rather peculiar. Most people think it derives its impressive growth rates (see chart below) from its cheap labour costs which make its products globally ultracompetitive. Certainly China has based its growth strategy largely on exports but far from being labour-intensive, its economy is rather capital-intensive.

This is well evident from the graph below. Investments as a share of GDP have grown enormously over the past thirty years and have become the main determinant of growth after the crisis when exports started declining as a consequence of the slowdown in Europe and US.

This is well evident from the graph below. Investments as a share of GDP have grown enormously over the past thirty years and have become the main determinant of growth after the crisis when exports started declining as a consequence of the slowdown in Europe and US.

But there is another striking feature in the Chinese economy that needs to be noted: the extremely low and declining consumption rate. This is by far the most worrying sign of a profoundly unbalanced growth strategy. Why? Thinks of it this way: China has both an extremely high investment rate and an extremely big current account surplus. The only way such an outcome can be achieved is if domestic consumption is severely compressed. Because remember: there is an inescapable link between the trade surplus of a country and its saving and investment rates. How can consumption be so repressed? This is simply a consequence of the declining share of output that goes to the household sector that is mirrored by an increasing share going to the corporate and public sectors.

To put it in plainer terms: the Chinese workers receive a declining share of what they produce, the rest goes to the profits of the corporate sector or it is appropriated by the State. A large chunk is then invested but not all of it: the overall saving rate of the country remains strikingly high. And this is what explains the huge trade surplus.

The walking debt

This very unbalanced distribution of income has led China to rely on two very unstable sources of growth: investments and trade. And to compromise the most stable source of growth: domestic demand.

As the leading scholar on the Chinese economy, Michael Pettis, has often argued this very unbalanced development cannot and will not last because it rests on one hand on the ability of the rest of the world to absorb a growing amount of Chinese goods and savings; and on the other hand on the possibility to find profitable investment opportunities at home.

The impressive investment rate has already caused the total debt of China to sore to incredible proportions: 245% of GDP in 2014, more than half of it in the hands of the corporate sector. From 2007 total debt has quadrupled, from 7$ trillion to 28$ trillion. The Chinese government has been subsidising investments, enabling the corporate sectors to obtain loans from State-run banks at very low interest rates. This has created more than one potential bubble, in the real estate as well as in the stock market.

As Bloomberg has noted: the median stock on Chinese bourses is valued at 95 times earnings, versus 68 at the height of the nation’s equity mania in 2007. And a sharp correction of the Chinese stock exchange appears to be under way. The Shanghai Composite Index registered a fall of 6.4 on Friday the 19th of June, which, according to market analysts, represents the worst downward adjustment since the financial crisis of 2008.

Combine this correction of stock markets with relatively lower expected growth rates: this year China’s GDP is supposed to expand by 7%, already 2 points below the average of the past 25 years and the rate is expected to drop to around 4/5% from 2016 onwards. The result of this combination is likely to be the emergence of a massive amount of unsustainable debt which slower growth will make very hard to repay.

Soft or hard landing?

The Chinese authorities seem to be fully aware of the problem and in many occasions have expressed their intention to rebalance the economy, towards a more limited reliance on investments and export and a stronger boost of domestic demand. The problem is that they have been saying this for at least ten years (according to the account provided by Pettis in its book The Great Rebalancing) but instead of growing, the consumption share of GDP has kept falling!

Now with the slowdown and the stock market corrections, observers are asking themselves whether the wake up call is imminent. And if it is, will it be followed by a hard or soft landing? In other words, how is China going to cope with an unmanageable amount of debt and a shrinking economy?

What China needs to do is surprisingly similar to what some Eurozone countries (above all Germany and The Netherlands) need to do: push up its consumption rate, lower its saving rate in order to increasingly rely on domestic rather than foreign demand. Some evidence is there that the country is indeed trying to pursue this path, which first and foremost requires rising workers’ wages and a more equal distribution of income. If the slowdown of the Chinese economy is indeed combined with such rebalancing it might actually be beneficial for the whole world, as growing Chinese demand would stimulate the economies of its trading partners. A reversal of Chinese current account surplus would mean a reduction of current account deficits elsewhere in the world, by definition.

There will certainly be problems of industrial restructuring as some sectors would suffer and therefore shed labour. Unemployed workers will have to be redeployed in other industries. At the same time mountains of bad debt will have to be either written off or transferred onto the balance sheet of the government – as it happened in Japan. China has surprised the world with its capacity to centrally drive its economy, climbing the global income ladder and securing spectacular growth rates for many years.

Will the Chinese government be able to face this coming challenge or will it succumb like many others before? The answer to this question will probably determine whether or not the world is going to experience another brutal economic crisis.