Greece, a tragedy

Economy 26 January 2015At the time of writing, the elections in Greece have not taken place yet: however, we thought it could be useful to review the story so far. We’ll do it following one of the many things the Greeks have invented: the tragedy.

I. Prologos: of public vices and private virtues

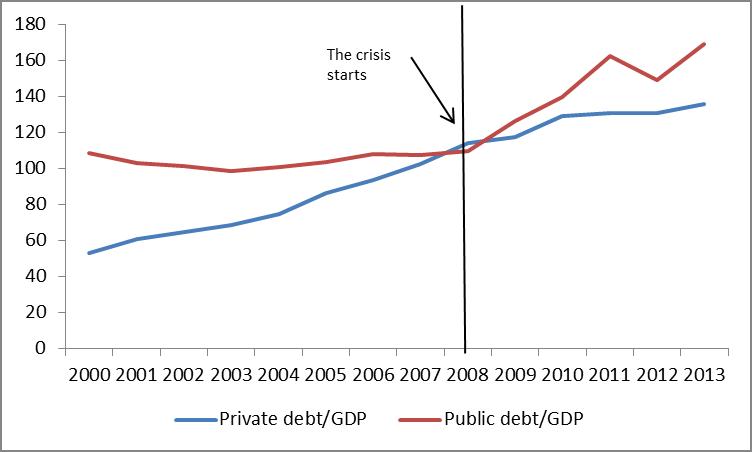

The usual narrative of the Greece current economic situation stresses that the Greek government went on a spending spree in the years after the accession to the euro. This created an unmanageable amount of public debt. So the crisis that Greece is living is mostly the consequence of irresponsible politicians which mismanaged public finance and lied to the EU Institutions about the size of the deficits. Judging Greece politicians is a prerogative of the Greek electorate; here we won’t indulge further on this. We will however point out a non-trivial detail that often fails to be mentioned: the exponential increase in Greece’s indebtedness – before the crisis – took place in the private, not the public sector. In the estimation of the ECB private debt increased by 217% between 1999 and 2007 while over the same period public debt over GDP increased by only 13%. The explosion of public debt over GDP happened after the Lehman Brothers shock as a consequence of deteriorating macroeconomic conditions.

The increase of private debt was connected to the deterioration of Greece external trade position: the current account deficit reached the huge level of -14% of GDP in 2007. As we noted before the accumulation of trade deficits translates into increasing foreign indebtedness: the country needs capital from abroad to pay for its imports. Economists generally consider 50% of foreign debt over GDP as “alarming”. Greece foreign debt was allowed to reach a level beyond 120% of its GDP.

II. Parados: how what happened, happened

Once again, the popular story about Greece’s troubles is that the excessive public spending went to finance current consumption rather than productive investments. We have already observed that it was rather a problem of private debt. Mutatis mutandis, then, private debt must have been used to finance unproductive investments. Or was it?

If one only looked at the GDP growth performance before the crisis, when this debt was cumulating, it would have been hard to blame the Greeks. Real GDP in Greece grew by a cumulative 33% between 2000 and 2007 against an EU average of 16% and a German’s result of 10%. If you have not lent money to Greece over those years, you may be excused for not knowing that indeed a substantial part of the borrowed money went to finance private consumption.

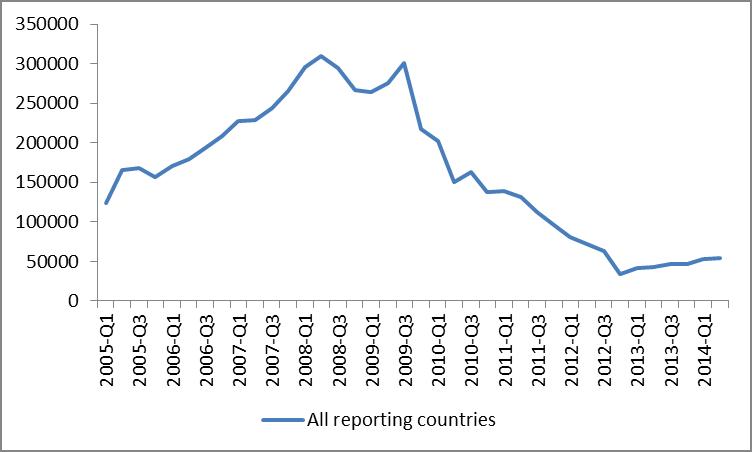

However for every borrower there must be a lender and it is normally up to the lenders to evaluate the risks and benefits involved in their investment. Foreign banks happily lent to Greece an enormous amount of money up until the moment of the crisis, as the following figure shows.

Similarly, for every importer there is an exporter. Greece’s private debt was increasing as its trade balance was deteriorating: almost 60% of total Greece’s imports came from within the Eurozone (14% from Germany alone). In other words, foreign investors were making money thanks to Greece borrowing and foreigner exporters were making money thanks to Greece spending.

III. Stasimon: why what happened, happened

In Greek tragedies there comes a moment where an external chorus intervenes to explain the plot. In this case we dare to disturb two dead economists, Bela Balassa and Paul Samuelson who will be our singing voices. The so-called Balassa-Samuelson effect essentially predicts that a country which is experiencing high growth rates will tend to have also relatively high inflation and this will produce an appreciation of its real exchange rate.

To be concrete, take Germany and Greece over the period prior to the crisis. Greece was growing faster than Germany, because it was “catching up” as expected within the European integration process. With higher growth rates there tends to be higher inflation, always in relative terms of course. This meant that Greece appreciated its real exchange rate vis-à-vis Germany. Now extend this to the euro area as a whole: Greece has been appreciating its real exchange rate versus most of its main trading partners. As a consequence the country saw a deterioration of external competitiveness and a worsening of its trade deficit.

If Greece had had its own currency, this pattern would have ended up with depreciation of the nominal value of the Greek currency against the currencies of its trading partners. Simultaneously, countries running a trade surplus would have experienced an appreciation of their currency. This would have put a limit to the size and duration of the trade deficit of Greece simply because with a depreciated currency, foreign goods would become too expensive to be imported; at the same time domestic goods would have become cheaper and therefore their exports would have increased.

But Greece had the same currency of its main trading partners. This had the effect of neutralizing the currency “signals”: foreign goods were not becoming more expensive and domestic goods cheaper. And it also had the effect eliminating the “exchange rate risk” which limits the amount of money foreign investors are willing to lend because they fear that at some point a devaluation may come. The euro created the appearance that any lending to Greece was risk free, so Greece could keep accumulating trade deficit after trade deficit, external debt over external debt.

Could this have been prevented? Balassa and Samuelson are long dead so we could not count on them. The Stability and Growth Pact does not foresee any monitoring of external or private indebtedness and complete capital mobility in the EU means that there were no limits to what banks could lend to Greece. The last two problems have been now recognised by the Macro-economic imbalances procedure and by the Banking Union. But for Greece, this all came too late.

IV. Exodus: the great escape

The crisis tore down the veil that was concealing Greece’s unsustainable debt levels and this in turn made private investors panic.

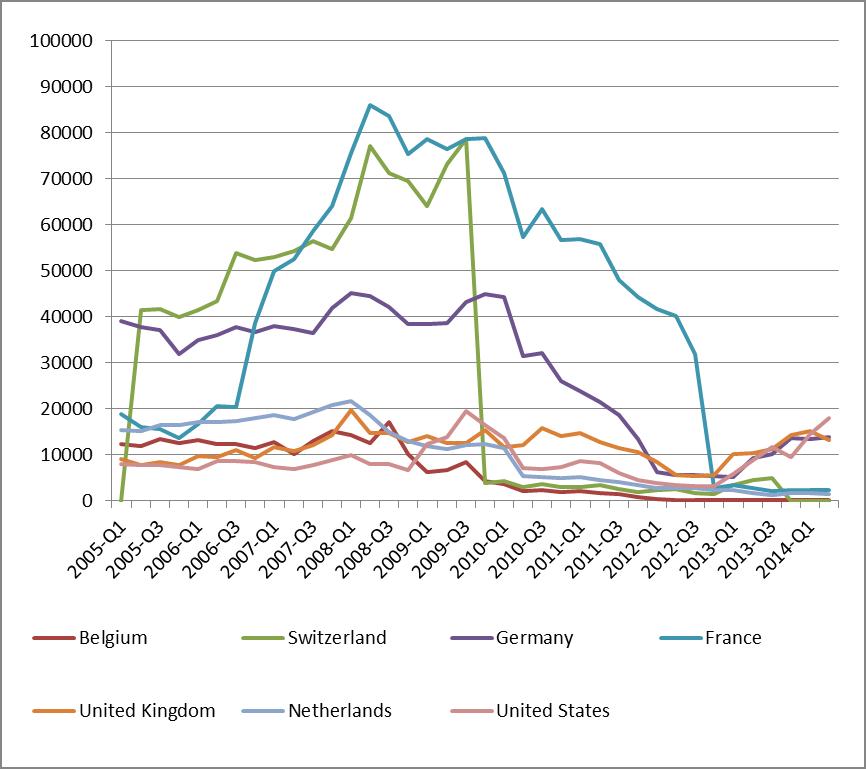

The first thing that happened was that commercial banks throughout Europe started selling off their Greek assets in order to get out of the danger zone. The countries more exposed to Greece debt were France, Switzerland and Germany (considering public debt only, Germany was actually first). As the next figure shows, it took them more or less time but by 2012/2013 private banks of these three countries had reduced to extremely low levels their exposure to Greece. And so did most of the other foreign lenders.

Foreign Banks exposure to Greece based on reporting country, millions of dollars – Source: Bank of International Settlements [Note: Switzerland data are affected by changes in accounting definitions].

Many observers have argued that the country needs a debt relief. However, one important aspect to consider is that the governing law of the Greek debt has changed. While previously the debt was issued under Greek law, it is now under foreign law. This took away one option for Greece, notably the method used by all western countries to reduce their mountain of debt after the II World War: inflation. This means that even if Greece restored monetary sovereignty by leaving the euro, the new “institutional debt” issued under foreign law would remain denominated in a foreign currency. Any debt relief should therefore come through a partial or complete debt restructuring.

Another option for Greece would be to push forward the internal devaluation strategy pursued so far under Trojka supervision. However besides being evidently less and less politically sustainable, the strategy has so far not yielded any meaningful result: the country has not resumed growth, nor was it able to boost its export sector. This means that the sustainability of the debt would remain anyway at high risk.

It really looks as if something impossible will have to happen to bring Greece back from the abyss. But after all, impossible things happen all the time in Greek tragedies.