EU Defence Budget Explained

Economy 28 February 2018The integration process within the security and defence areas, in a modern sense, dates back to the post World War II period. It involved the international organisations, institutions, (in)formal consultative forums and other international bodies, established in line with the United Nations Charter, under the guaranteed right to individual and collective defence. Since the Charter entered into force, there have been dozens of such multilateral arrangements. The bilateral agreements signed by almost all countries of the Eastern Bloc are particularly interesting.

The Common Defence and Security Policy of the European Union (EU CSDP) presents a unique type of supranational integration within the security and defence areas. The EU common defence issue has been hindered from its very beginning, since the NATO presence was following the integration process in defence (and mainly in security) area. Every significant attempt initiated by the European side to further integrate in defence was heavily oppressed by the transcontinental partner – the US. Ever since the EU CSDP has been formally established, the EU Member States have further brought to the agenda the integration in the most likely last field of cooperation – defence. Nice Treaty adopted in 2001 did not however move this issue to the “high level politics”.

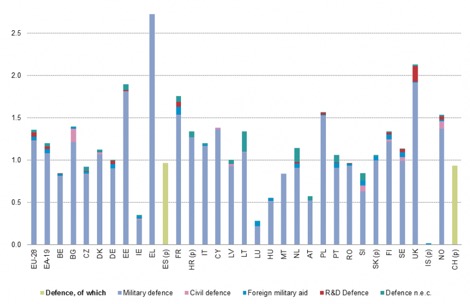

What’s in stake with the budgeting issues for the EU defence? The EU defence budget is de facto formed by the national defence budgets and the supranational (EU level) defence budget. In total, including the 28 Member States’ contributions, the summed budget is dramatically high. According to the EU methodology of assessing the defence budget, it consists of: pure defence expenses, civil defence, foreign military aid and R&D defence expenses. Even though most of the EU Member States are also enjoying the NATO membership status, they do not respect the 2% rule. According to this rule, all the Member States must have at least 2% of their total national budgets dedicated to the defence area. In 2016, Greece was the only country which respected the 2% rule, spending the 2.5% of GDP for military expenditure.

According to the Eurostat, in 2015 the highest levels of total expenditure on defence in the EU and EFTA countries were observed in Greece (2.7 % of GDP), in the United Kingdom (2.1 % of GDP), in Estonia (1.9 % of GDP) and in France (1.8 % of GDP). On the contrary, Luxembourg (0.3 % of GDP), Ireland (0.4 % of GDP), Hungary (0.5 % of GDP) and Austria (0.6% of GDP) had comparatively low expenditure on defence. Iceland reported the lowest level of expenditure, as it does not have a standing army (0.0 % of GDP and 0.05 % of total expenditure).

At the level of the EU–28, the major part of the defence expenditure is concentrated in the COFOG group military defence (1.2 % of GDP in 2015). While the civil defence reported less than 0.05 % of GDP. Research and development on defence made up a negligible part of government expenditure in all countries, except in the United Kingdom (0.2 % of GDP) and in France (0.1 % of GDP). Foreign military aid amounted to 0.1 % of GDP for the euro area, with notable amounts in Germany, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Finland and Sweden (all at 0.1 % of GDP).

Beyond the launch of the European Defence Fund, €40 million are budgeted in order to finance a collaborative research in innovative defence technologies and products. With €25 million already allocated in 2017, the total EU budget devoted to defence research until 2019 amounts to €90 million. In 2018, the EU defence budget will slightly grow in comparison to 2017 and 2016. The overall supranational EU budget is being in constant growth, ever since it was “formalised” in the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon. It remains to be seen how defence budgeting will develop in light of the constantly challenging neighbourhood of the 28 Bloc.