Sustainable urban mobility: a new metropolitan lifestyle

Energy 13 July 2015In the last years, the European Union has been largely investing in urban sustainable mobility, sensitizing public opinion on the importance of a sustainable and integrative approach to urban mobility. In this sense, the Action Plan on Urban Mobility (2009) and the Transport White Paper (2011) are officially showing the path for our metropolitan lifestyle.

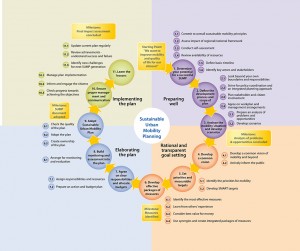

Opposite to the traditional inductive approach, the new European trend demands public legitimacy that results from the active involvement of stakeholders and civil society. Moreover, it urges for coordination of policies both among public authorities and specialised sectors (transport, land use, environment, social policy, health, energy, economic development, safety, etc).

Through the participatory approach, the citizen is at the centre of the plan, allowing a broader picture of the issue. Indeed, while the approach was traditionally sectorial, nowadays the focus is on complementarity, i.e. on the system: it is a holistic vision, with a long-term tactic and the evaluation of side effects.

What are the main points?

- The EU plan encourages a shift towards more sustainable modes, fostering a balanced development of all relevant transport modes, i.e. public transport, walking and cycling, intermodality and door-to-door mobility, intelligent transport systems (ITS).

- In view of the participatory approach that characterizes EU current policies in general, a commitment to sustainable mobility is required to all levels of government and relevant authorities, as well as to civil society and private stakeholders.

- While the strategy encompasses a long time framework, the EU recognizes the importance of short-term objectives to assess current and future performance and, if deemed necessary, to fix policies. A Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, indeed, has to set measurable targets, based on a realistic assessment of the baseline and available resources.

- The last feature of the plans to get to a sustainable urban mobility is the broad approach, meaning that sustainable mobility takes into account all costs and benefits of the adopted mix of transport modes on human beings and the environment.

Beyond the mere effects in terms of urban traffic, the overall objective of the adopted policies should be an improved quality of life. There is strong evidence that sustainable urban mobility improves the quality of life in an urban area: well coordinated policies result in a wide range of benefits, such as less time for commuting, more attractive public spaces, improved road safety, better health, less air and noise pollution. Moreover, reduced congestion has economic advantages, such as the reduction of oil costs and CO2 emissions. Furthermore, non-motorised transport contributes to a healthier life and a mix of modes increases efficiency.

This is not just “good theory”, but in some interesting cases this model has proven to be efficient.

The Parma case, developed before the 2009 EU Action Plan, perfectly proves the feasibility and the advantages of the European theoretical framework.

PARMA – an integrated Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan

Parma is a medium-sized city (about 200.000 inhabitants) located in Northern Italy. In 2005, the Municipality of Parma started an integrated urban transport and land- use planning process that included: a Urban Mobility Plan (PUM), which is more or less a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, a Urban Traffic Plan (PGTU), and a land use plan (PSC).

Drafting the two transport plans (the PUM and the PGTU) together has encouraged connections between the short term actions promoted by the PGTU and the demand management policies and the infrastructural projects that are part of the strategic scenario outlined by the PUM. This strategy enables to assess current and future performance, as predicted by the EU.

Moreover, the drafting of the two plans in context allows for a broad approach, i.e. a consistent and articulate strategy of mobility management that is able to coordinate the demand on different transport modes and the different services provided both to private and public mobility (focus on walking, cycling and disabled people). Again, that is exactly what the EU asks: a balanced development of all relevant transport modes.

The drafting of the PUM was addressed in three phases.

Phase 1 was aimed at understanding the urban area and its transport system and was carried out consulting the wide database provided by the municipality. The outcomes of phase 1 were:

- highlighting the most important critical points of the transport system (congestion, environmental impacts and road casualties);

- defining a transport and land use reference scenario (consisting of interventions coming at a late stage in the decision-making process).

While the typical participatory approach is usually led through round tables, Parma has opted for a – let’s say – “indirectly” participation through a database. Apparently, it fulfilled its goals, though.

Phase 2 was focused on setting up and calibrating a transport model (ME PLAN) and on the definition of plan scenarios. Two alternative plan scenarios were defined. On the one hand, the land-use scenario included interventions promoted by the current land-use plan along with the interventions of the reference scenario. On the other, the sustainability scenario promoted policies and measures aimed at reducing the negative environmental and social impacts of the transport sector, combined with the interventions of the reference scenario. For all the interventions included in the two scenarios, timing (short, medium and long term) was specified in order to allow the coordination of the PGTU actions (short term) and the PUM policies/measures (medium and long term).

Phase 3 was aimed at achieving the municipality’s selection of the plan scenario. The MEPLAN model was used for simulating the transport, environmental and economic impacts of the selected scenario. The plans are based on the following measures: road vehicles regulation in the city centre, extension of control and safety actions in sensitive areas of the city, traffic calming, promotion of cycling and pedestrian modes, integration of public transport modes and bus priority. This is determinant for the evaluation: the scenario has short-term and medium-term indicators for an effective monitoring of the plan implementation. Plus, the selection of different measures demonstrates Parma holistic approach: the plan tackles safety issues, traffic, healthy life, environment, etc.

In a sense, the new concept of sustainable urban mobility is just an aspect of a new culture: a vision that goes beyond transportation and involves all social aspects of urban living. Involvement of stakeholders and citizens is a basic principle of a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan. A city government that cares about its citizens’ needs and that involves its stakeholders appropriately will obtain a high level of “public legitimacy” and will reduce the risk of opposition to the implementation of ambitious long-term policies.

So far, the strategy is winning… Maybe, in the next future, apps such as beatthetraffic will be ancient history.